Since I am not a European man in the 18th Century, my Grand Tour after earning my architecture degree has agreed to be conquered piecemeal. My first foray was to Berlin in 2024, where I accidentally booked a tour of the Bauhaus entirely in German then ate at a restaurant called “Döner Kebap am Bauhaus.” Not to worry, because everyone in Berlin (and Dessau) seems to speak perfect English, while insisting their English is “not so good.” The second stop on my tour led me to Barcelona two years later, where, again, everyone speaks perfect English, but with a hint of a British accent. My high school diploma says I’m bilingual, but my first foray into a Spanish-speaking country said otherwise.

My partner and I arrived in Barcelona on a weekday in the middle of January. In contrast to Southern California, one of the richest places on the face of the planet, public transit is widely available and intuitive in many European cities. My hotel (not-so) coincidentally happened to be off the Sagrada Família TMB Metro station. As I carried my suitcase up the steps of the station exit, my body shifted to one side and rattled my carry-on loudly onto the tile sidewalk, a rite of passage. Thankfully I had the foresight to turn around, catch my breath, and stumble backwards a bit as I found myself at the base of the tallest church in the world.

View from the Sagrada Família TMB Metro Station. Image courtesy of the author.

Gaudí lived in the workshop at Sagrada Família until his death where, tragically, he was run over by a tram on the jobsite (to this, my coworker responded that “we used to be real architects”). Despite meeting God via public transit, Gaudí could not have predicted that a viewer’s first impression of Sagrada Família might be emerging from a dark Metro station, that a tourist arriving from the airport might squint at Google Maps in front of the Passion Façade one hundred years after his death. In the short time that Antoni Gaudí had to devote his life’s work to Sagrada Família, he undoubtedly earned himself a place in the architectural canon. He knew he would not live to see the church completed, but through his focus he preempted funding, project pauses, project abandonment, and views from across the street. Gaudí’s early work, such as at Casa Vicens, was heavily influenced by the proliferation of the camera and greater availability of photography. With this in mind, Gaudí planned for three parks each the size of a city block to neighbor the church, so it could be admired and captured by throngs of tourists on an iPhone from afar. Gaudí devoted 43 years of his life to working on Sagrada Família, and left future scholars with ample material in the form of physical models and sketches to complete his vision.

My time in Barcelona had me waving hello to Sagrada Família for a week, like a waypoint in the skyline. The height struck me, and so did the ways in which it differed from the polished textbook images, the ones I memorized in high school AP Art History. It seems that Sagrada Família has had two distinct lives: one under the watchful eye of Gaudí, and one with the city of Barcelona. This story is inadvertently expressed on the façade, where the Nativity Façade, the only one completed under Gaudí’s supervision, has a distinctly different style than the Passion Façade, or the rest of the church for that matter. The Nativity Façade has distinctly organic, art nouveau sculptural elements familiar to Catalan modernism of the time, with realistic human figures and ornament.

Massacre of Innocents scene on the Nativity Facade, completed under Gaudí’s supervision. Image courtesy of the author.

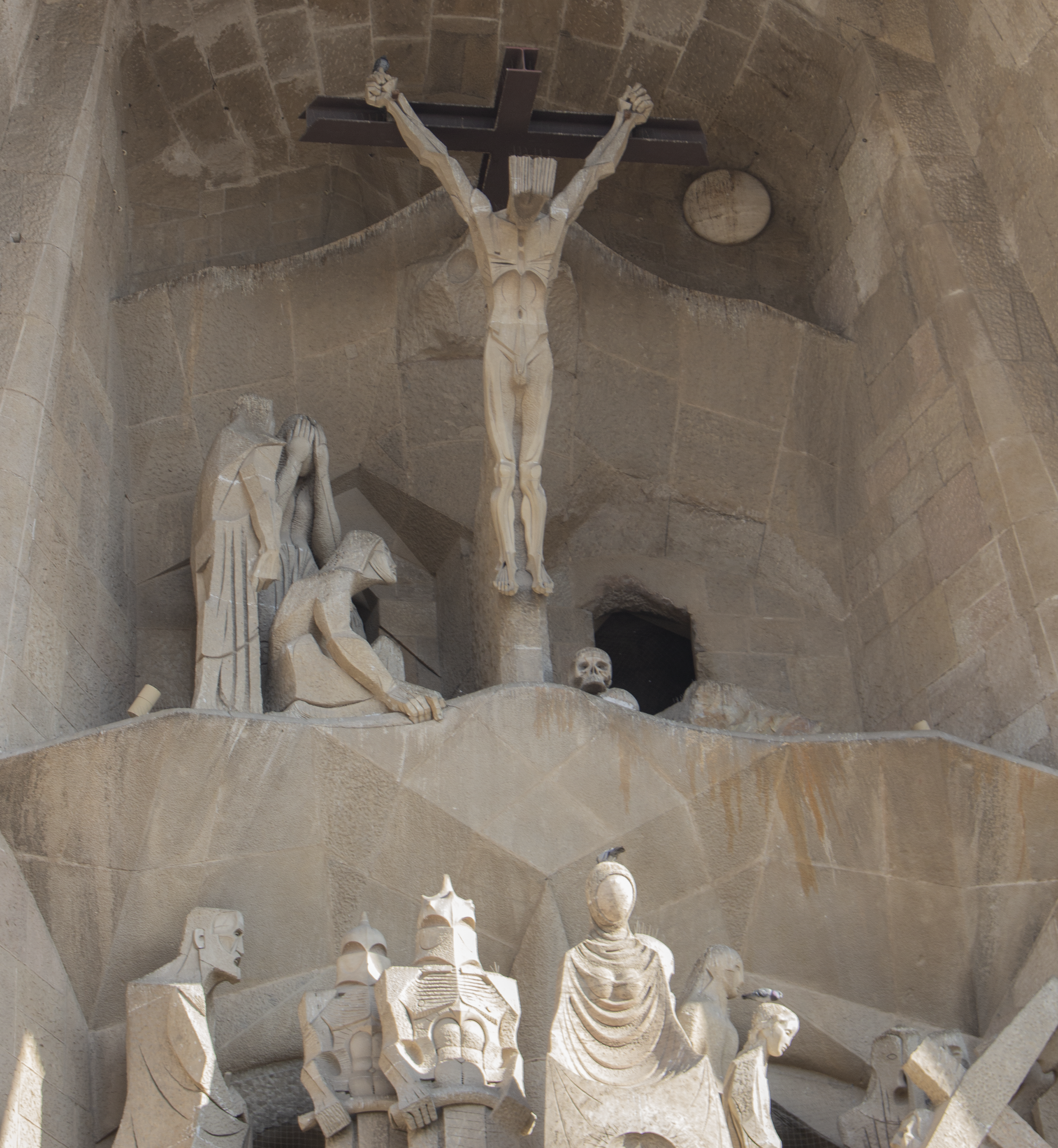

Sculpture on the Passion Façade, on the other hand, resembles Medieval Romanesque sculpture, with noticeably abstracted human figures and motifs. The crucifixion takes place on weathered steel I-beams, with a memento mori at Christ’s feet. Our tour guide explained that the different art styles can be understood through Christ’s birth and death on the two main Nativity and Passion Facades, but it’s hard to ignore a one-hundred year shift in taste, craftsmanship, technology, and modeling techniques.

Crucifixion scene on the Passion Facade. Image courtesy of the author.

In 2019, Sagrada Família finally earned a building permit from the city of Barcelona after 137 years of unpermitted work. Today, the neighborhood surrounding Basilica de la Sagrada Família is entirely obsessed with Antoni Gaudí. The neighboring street is called Avinguda Gaudí, diagonally slicing through the regular grid of Barcelona. It’s lined with shops like “Sweet Gaudí,” “Gaudí Gelats,” “Gaudí Shopping,” or “Sagrada Tapas.” One of my favorites was a coffee shop called “Mozart Gaudí;” unfortunately, Mozart and Gaudí missed each other by about a thousand miles and a hundred years.

MOZART GAUDÍ, Av. de Gaudí, 60, Eixample, 08025 Barcelona, Spain. Image Courtesy of the Author.

Sweet Gaudí, Carrer de Lepant, 312, Eixample, 08025 Barcelona, Spain. Image Courtesy of the Author.

There is also a row of quick service restaurants - McDonalds, Ben & Jerrys, Taco Bell, and Five Guys - directly facing Sagrada Família. They keep the lights on longer than the church as well; when the towers go dark promptly at 10pm, Ben and Jerry are there with open arms. Souvenir shops also line the block with technicolor casts of Sagrada Família and, for some reason, so many images of French Bulldogs on tote bags and t-shirts. Unfortunately the souvenirs inside the official Sagrada Família Gift Shop were uncharacteristically tacky as well, I didn’t bring home a single magnet, or salt and pepper shaker reproductions of Gaudí’s towers.

If you’re not diligent, a trip to Barcelona can quickly turn into a Gaudí Disneyland. The architect was prolific across the city, with numerous official and unofficial tours offered for each historic site. Admittedly this could be a great way to spend a week - Gaudí really was one of the greatest architects of all time - but some businesses in Barcelona have learned to slap his name in the title and generate traffic. In many ways, Sagrada Família itself has evolved into a temple to its architect, rather than to God; our tour guide revealed to excited gasps that Gaudí was buried in the crypt below us and we peered around one another for a glimpse at greatness. Meanwhile, Gaudí was a sincerely pious man who has been put on the path to Sainthood by Pope Francis early last year. Personally, I can’t wait to welcome the first Saint who was a licensed architect.

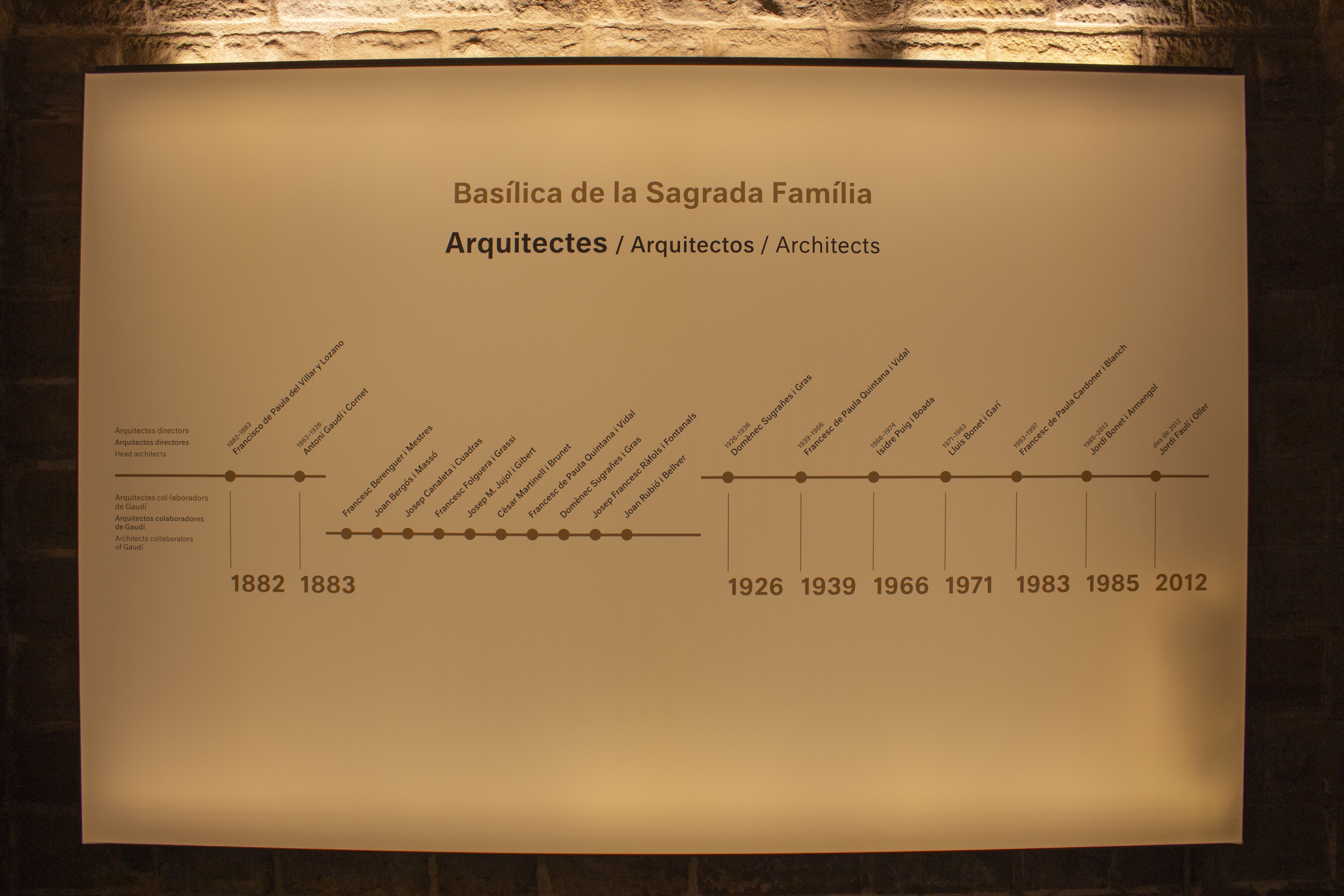

At the very, very, very end of the Museum, underneath the main basilica and just before the gift shop, there are two illuminated displays listing the chief architects and sculptors who have worked on Sagrada Família since its inception.

Attributed architects and sculptors at the The Sagrada Familia Museum. Images Courtesy of the Author.

The current Chief Architect is Jordi Faulí i Oller, who was born in Barcelona himself. He joined the team in 1990, originally assisting with the structural analysis and 3D modeling of the church when it was an emerging technology. Faulí was elevated to Chief Architect in 2012, and in 2026 he is hoping to be the architect who brings the church to completion. Though dim and poorly placed, this display is significant for recognizing the immeasurable efforts of those other than Gaudí. The list of sculptors is slightly longer than the list of architects, though in more questionable order. Notable on this list is Etsuro Sotoo, a Japanese sculptor who ultimately completed the sculptural elements on the Nativity Façade, and two sets of highly detailed bronze doors with cameos of bugs, leaves, and other critters. Nowadays, this is where the English tours begin.

Detail from the bronze doors at the Nativity Façade, designed by Etsuro Sotoo. Image courtesy of the author.

While Gaudí awaits sainthood from the crypt, hundreds of workers, craftspeople, architects, and researchers continue their work on Sagrada Família. The tallest spectacle of the church, the Tower of Jesus Christ, is aiming to finish construction this year as it rises towards the heavens, marking one-hundred years since Gaudí’s death. Admittedly when I visited, the pinnacle four-armed cross was already perched unceremoniously on the tower.

Sagrada Família exists in a very different urban and social context than when it began construction. When Gaudí’s work began in 1883, the first woman to receive an architecture degree in Spain wasn’t due for another fifty years. The temple exhibits this immense passage of time on its façade, with different sandstone colors, style of sculpture, and wear. It has stood witness to Barcelona’s history for over a century, and I am aware of the privilege to experience it in a singular moment as it reaches completion. With any luck, and the hard work of people that may be lost to time, Sagrada Família is due to be completed later this year. Time might stand still, and we’ll find out if architects go to heaven.

A worker on the Passion Façade. Image courtesy of the author.

Aryana Leland is a designer based in Denver, Colorado. She studied Architecture + Art History at Cal Poly Pomona, and her current interests are the Colorado Rapid Response Network and Joan Miró.

All opinions are my own.